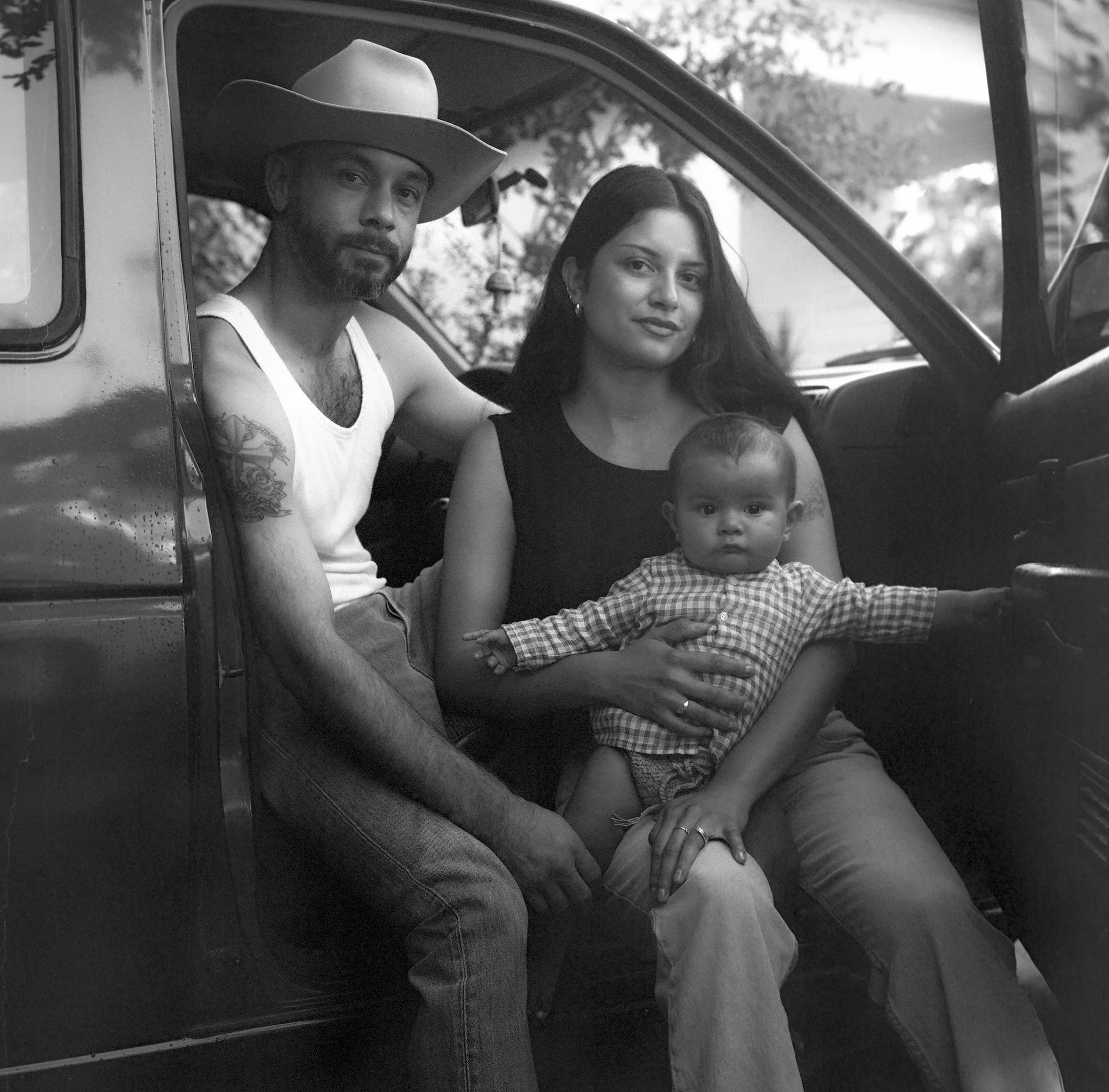

KEN TAYLOR

I mean, you try to be a good person and try to be honest. I think that's the job of an artist, and sometimes the truth isn't beautiful. It's not what everyone else is doing sometimes. I think that's where the radical part is. Where to be different and not for the sake of being different, but just for the sake of trying to be your truth.

— KEN TAYLOR

A Man Apart: Ken Taylor finds his roots through separation.

words BY IAN RANDLOPH images by David Katzinger

Some turn to the past for inspiration, others for destruction. But woven between those extremes are images that capture moments in our own time, moments we can’t forget. Whether uplifting or painful, they shape how we understand who we are today. The clothes we wear, the places we’ve been, the things we do, these are snapshots of the present, but like the past, they’re never fixed.

Bakersfield-raised and now Chino-based artist Ken Taylor sees these fragments of time as symbols of a life always in motion. For him, history isn’t something to cling to, it’s something to learn from. His perspective isn’t about influence for influence’s sake, but about how these moments push us to think, adapt, and grow. While history belongs to all of us, his work adds another layer to the conversation where art, like ourselves, is continually headed.

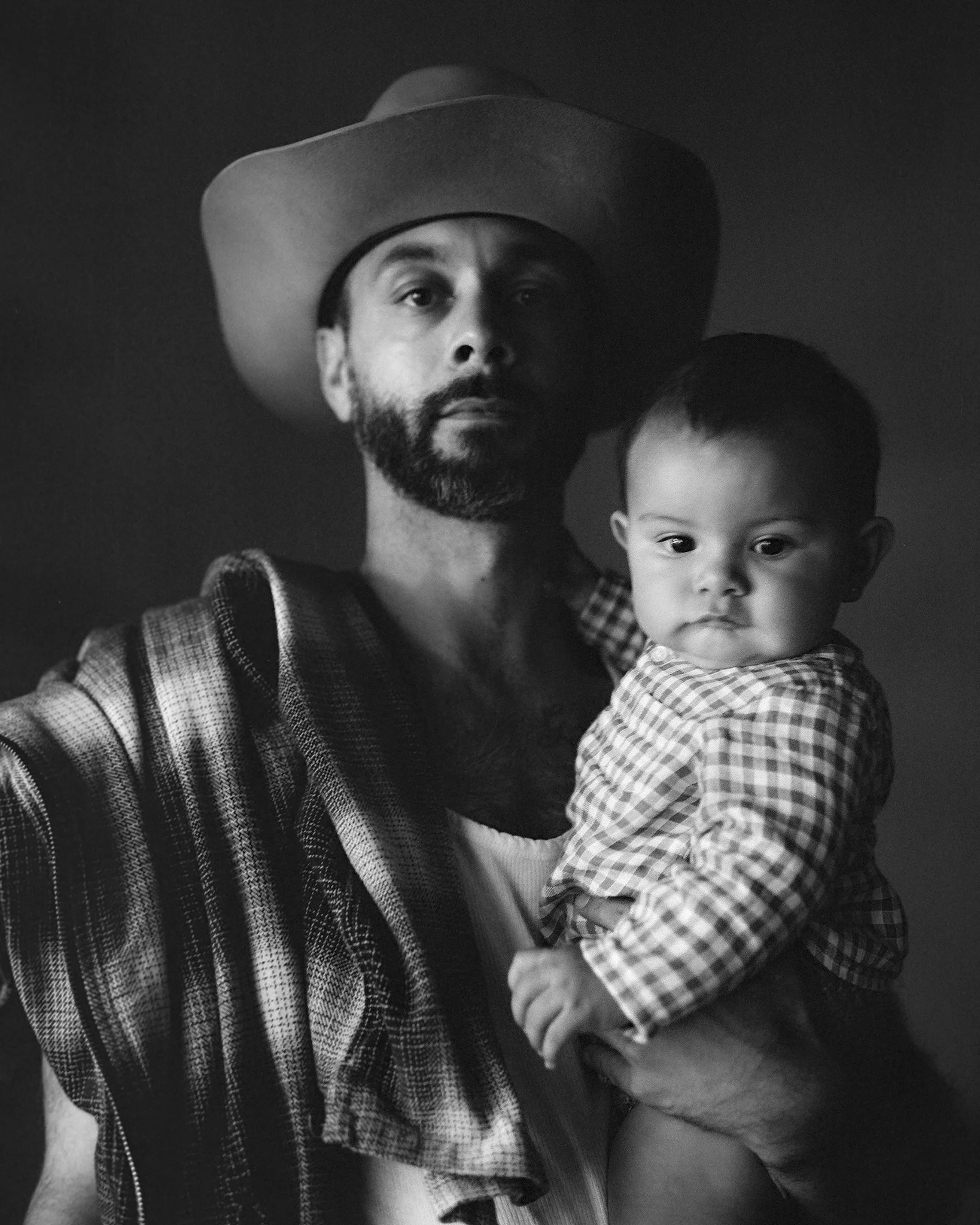

Ian Randolph: How has having a family changed how you approach your art?

Ken Taylor: I mean, the obvious things. Yeah, you want to spend more time with your family, you know. It's funny, there are two worlds for me. It would be my art world of creating, then it would be reality. Now having a family, it's like you kind of have to smash both of those in one.

I think having a child helps you remember how to be a child.

I'm doing these things, and then before having a family was like "Okay. Now I'm separated from that". I'm like, in reality now as an adult. You don't have time to be disconnected from reality like that. I think the biggest difference for me has been not dissociating myself from creating.

IR: How did your upbringing inform you artistically?

KT: It didn't. I wish to think of my parents as artists, but they never knew that they were. I grew up with my mom, who has always been an entrepreneur. I remember helping her sell oranges at the swap meet. I remember tinting the windows of our van with spray paint because we had to get creative. The sun was too hot, and for the oranges, which needed to be dark, so they'd last longer.

My stepdad was a mechanic, so he was like the ultimate MacGyver. The guy is just in a shop with tons of tools and open engines. I'm just sitting there, and then you learn that as a mechanic, it's about fixing and diagnosing.

There are all these tricks about how to find a way to figure out what's wrong with the car, and it's like that with sculpting.

Like a Chris Burden kind of art vibe that I got after learning about this guy. I was like "Whoa! My stepdad is like this guy...". That was more of my upbringing. Yelling in Bakersfield, selling oranges, and the mechanic shop. When I got to college, that's when I started thinking about becoming a painter. I never really liked to focus on art or something until I got a little better at it.

IR: Where did you go to school?

KT: Cal State Bakersfield. I went there actually on a soccer scholarship, and then I ended up taking an art class with this professor named Sarah Vanderlip. I felt like I could do this after taking her class. I felt the same feeling I felt when I talked about the way I grew up. Dude, I grew up in a house with broken washers and dryers in the front yard... It was crazy, so when I saw this, I was like "These people are doing this art like this?!". I'm gonna just spend my time trying to do art, and I need to study. You have to find something to study, and then through that, I met Mary Weatherford, who had a show in Bakersfield. After that, I grew up doing a little bit of upholstery. She did an artist residency at Cal Bakersfield and she needed help stretching canvases. I ended up being good at it because I used to stretch couches, so painting is way easier. She asked if I wanted a job. At first I said no and I went to Europe for six months... When I came back, I said OK. I needed money. I needed a job. That's when I moved to LA. That is where I learned more about painting.

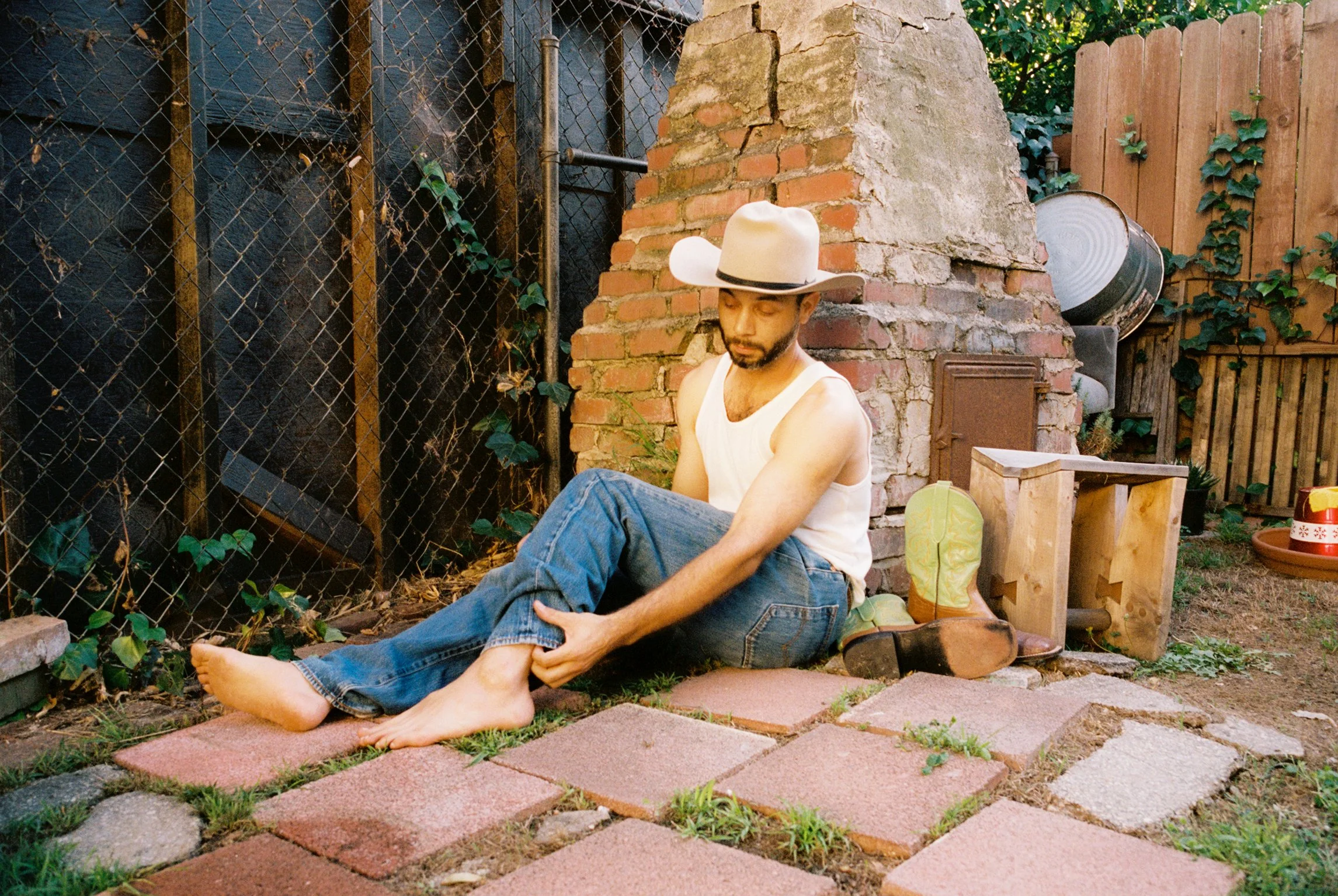

IR: I've noticed that some of your art involves symbols relating to things that are considered manly in a traditional sense (Cowboy hats, Cars, Canyons, etc.). Was that intentional, and why?

KT: I guess so. I shouldn't even be saying anything because I'm around the environment, and that's kind of what was coming out, but it's funny that you picked up on it before I even said it or thought about it.

IR: You have a lot of detail in your paintings that shines a light on the beauty of imperfection. Is that something you think about in your day-to-day life?

KT: When I go back to learning about painting from Mary Weatherford...She has a great knowledge of our history, and I think working with her, I learned more about that. She was taking us to New York because we had to install shows. We would just go walk around and look at our gallery in the studio. We'd talk about paintings and open up to take a pause. She was like "Okay. Pause on the history lesson. Go look at some paintings.". I think all that style and technique stuff comes from actually learning the history of painting. I'm layers of the light texture. It's not that I'm trying to be in the painting. Something that is going to look like what it is exactly. I'm trying to make a good painting. I use these symbols to kind of con in painting, you know what I mean? It's less about the symbol than it is, but the symbols are just there. Just like an anchor for me to kind of hold onto something in this abstract world of painting. How am I going to dig myself out? I'm trying to focus more on what I can do, and what I can do is make something that someone can look at to maybe help them feel a little inspired or see something that they hadn't seen before.

Looking at nature is sometimes like painting. I call it the art goddess. It's kind of like this idea of consciousness. It's what makes us human or something.

IR: That's true. I think there's so much pressure on artists and just people in general in that regard. They want to have their ideals or whatnot to make you this kind of someone with some sort of cultural impact.

KT: We're not! (laughs)

IR:. Do you ultimately want your art to have a cultural impact on society?

KT: When I was like 20 or something, I was like "YEAH! All right!" I had a friend who was super political, and he was always trying to tell me, "Oh, you gotta make something that says something." I tried to explain to him that I think being an artist is radical enough. No, but it's the fact that I'm choosing to get my job and not to get a job. I'm choosing not to work at a certain job just to buy a house. That part of life is full. Don't get me wrong, it could be full for a lot of people, especially in the arts and stuff like that.

I think when you choose this type of life, most people share the idea of you trying to create something to push the boundary of life, and just to show that it could be a little different.

IR: Yeah, it does take heart to do something like this. What are the key fundamentals in your life?

KT: That's the point. It's not to have those. Try to break them. When you find yourself following something, there's another way to do this.

I mean, you try to be a good person and try to be honest. I think that's the job of an artist, and sometimes the truth isn't beautiful. It's not what everyone else is doing sometimes. I think that's where the radical part is. Where to be different and not for the sake of being different, but just for the sake of trying to be your truth.

That's a lot harder than we think. I'm saying to the core, we all are so unique. At the same time, we all look so much alike because of the way we were conditioned to do certain things. I think I'm trying to break out and not be so fundamental. Eating healthy and drinking a lot of water. Those are things I've made our fundamentals in my life.

IR: What does the desert represent to you when using it in your art?

KT: The desert is just more like California. We're surrounded by a lot of deserts, succulent plants, and things like that. I think of the landscape of nature in the arts. For a while, I thought some people could tell you what famous brands, logos, restaurants, chains, and stuff like that were. I think people can find it hard to point out what kind of tree is on the street or what kind of flower.

A lot of my art is learning. I'm trying to study. I'm birdwatching and I'm trying to make a sculpture of a bird. I'm just trying to learn what these things are, even if I paint a plant or something else.

IR: What are some essentials that define who you are?

KT: Music, dancing, and coffee. You know. Simple, simple things...

IR: What is the most valuable thing to you?

KT: Most valuable? Damn... What's the most valuable thing to me?... Mother nature, life, and health.

IR: What's been your proudest moment as a father?

KT: My daughter is kicking a soccer ball.

IR: It's in the blood...

KT: Oh, we're going to sign her up for sure! The proudest moment is just seeing as a father is her eating her food, and just every little kind of... What did they say? What do you call it when you?

IR: Milestones.

KT: Milestones! Each little milestone that she hits is like the latest milestone. Always a proud moment. It's so much fun.

IR: What does the future look like for Ken Taylor?

KT: Dude, the future is ancient... I think I'm gonna leave it at that....The rest of that is for you or for other people to think about!

Ken Taylor’s story is one of separation and connection, between past and present, art and life, self and society. His work turns everyday symbols into shifting markers of identity, memory, and growth, reminding us that nothing stays fixed, not even ourselves. In blending the personal with the universal, he challenges us to look closer at what we carry from our histories and where it might lead us next. To see how his vision unfolds, you’ll have to step into his art.